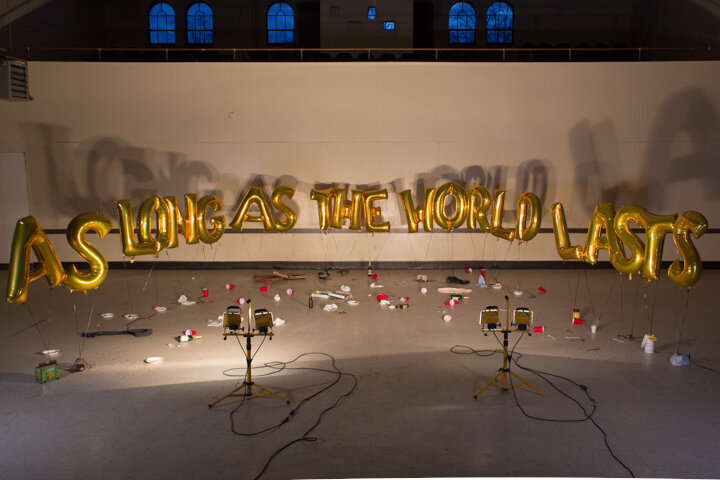

Untitled (AS LONG AS THE WORLD LASTS)

Untitled (AS LONG AS THE WORLD LASTS), installation views from work-in-progress at Sculpture Space, New York, 6’ x 32’ x 13’, 2019.

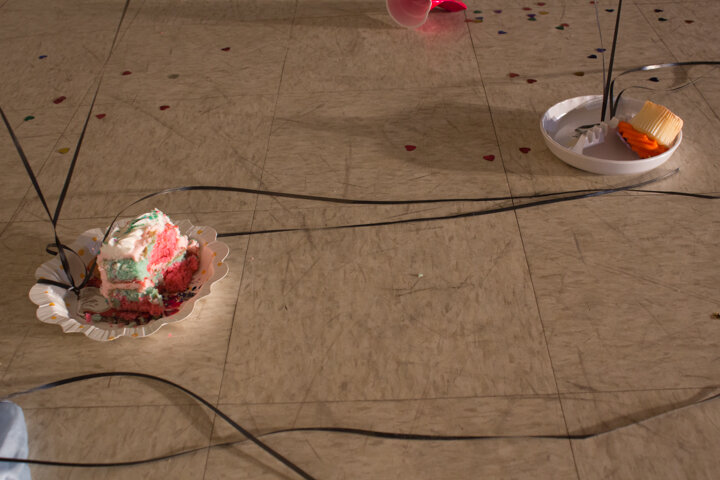

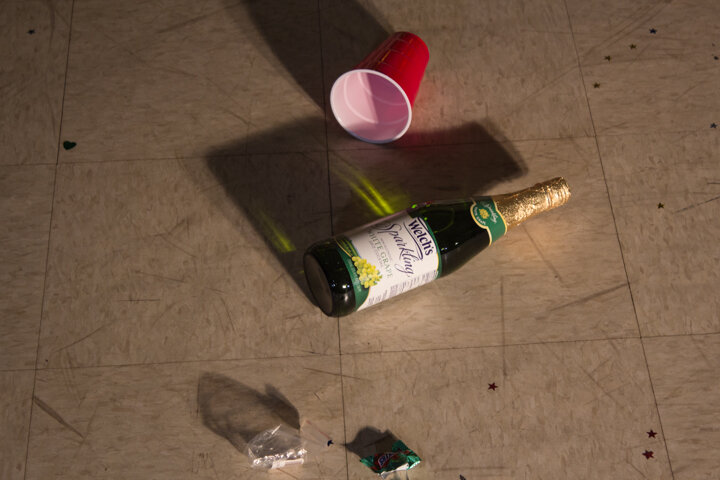

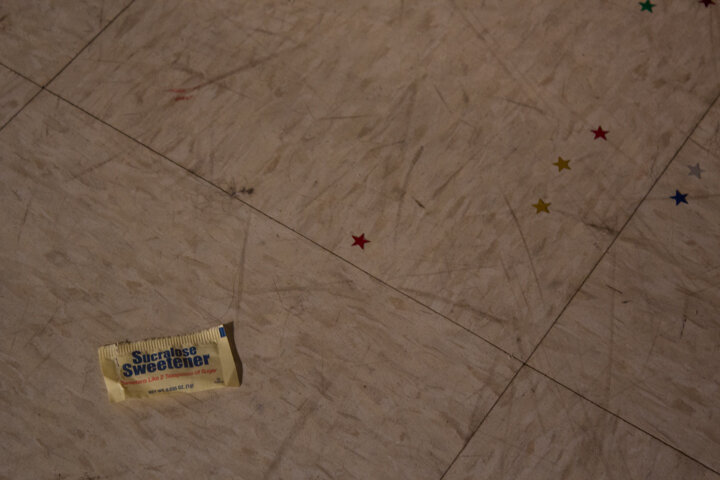

Materials list: 40-inch mylar balloons, helium, aromachemicals, halogen lights, extension cords, generator, 3 boxes of empty nonalcoholic beer bottles, 2-liter bottle of Diet Coke, 2/3rds empty, full-figured bra (2), men’s “tighty whitey” underwear, size small/medium (1), gold leafed party napkins, tacky round cake, plus-sized women’s “granny panties” (2), plastic plates & sporks in “closeout” colors, pizza+box+crusts, off brand box of tissues, sugar-free sweetener packs, ashtray+cigarette butts, metallic confetti.

Project Notes

Residue, inscriptions, traces, and evidence are similar themes that frequently recur in my work. They are by-products of an event or sequences of events that often imply a narrative. There is a collage element to reimagining the event by finding connections among the constituent parts of its residue that I find interesting.

Lately I’ve been thinking about the residue that is left after a party ends. After everyone leaves, what is there to glean from the residual sites, sounds, and smells? Parties are communal occasions that allow people to transcend time and lose themselves. Party like you just don’t care. Party like there’s no tomorrow. Party like it’s the end of the world. End of the world? What would a party at the end of the world—or more precisely, at the end of this world—look like? Pretty crappy if you ask me. Our world is characterized by a disappearing social space, in which connections between people have dissolved into only the most superficial bonds. No one seems to be responsible for it, therefore no one is to blame. But as social life becomes more insular, it also becomes more inbred; the absence of critical diversity and the generative antagonism that often comes with it leaves the social body compromised. As institutions, technologies, and entertainments algorithmically adapt to feed the specific tastes of individuals, those individuals become addicted to their private, subjective experiences. In other words, the party’s gonna suck because the guest list is too narrow. It’s in this context that I imagine the last party ever also being the worst party ever.

In fact, it was from this very proposition—What if the last party ever was also the worst party ever?—that I developed this artwork. I knew that the latter conceit, the worst party ever, was highly subjective. Indeed, I have several mental models of what a “worst” party might look like, and as I reimagine this installation for future venues, the “party residue” will change in each incarnation to point to new scenarios. What they all have in common is an unsustainably narrow list of guests who are united by little other than their unselfconscious desire to express their identities through the conspicuous consumption of products and the half-baked ideologies those products claim to exemplify. In this installation, you get the feeling that, in spite of interacting with each other, these party goers did not experience one another as much as they experienced an even duller version of themselves.

The central motif in this work is the phrase “AS LONG AS THE WORLD LASTS.” It is written in 21 helium-filled mylar letter balloons, some of which are designed to off-gas the scent of halitosis (bad breath) over the course of the exhibition. The phrase is the English translation of the Latin text, “QUAMDIU MUNDUS DURAT,” which I first encountered while reading Hannah Arendt’s book, The Human Condition. Arendt champions the active life (“vita activa”), a political position based on public activity that draws on the cosmology of the ancient Greeks and Romans. To be active in the world one must be in public, that literal and figurative sphere not created by God or Nature, but created by the work of men. Worldliness for her was a public domain built on the simultaneous presence of a plurality of perspectives. In order for the world to endure, the multitude needed to be active in public, speaking and listening. She contrasted this against worldlessness, a critical aspect of early Christian cosmology, which viewed the world as perishable, and therefore every activity engaged therein was engaged in on the condition as long as the world lasts. She pointed to other historical moments in which this condition of wordlessness had subsequently been embraced by Western culture, notably after the fall of the Roman Empire, and in post-war, 1950s era society. She predicted that worldlessness as a political phenomenon would inevitably dominate the political landscape, and for far more nefarious reasons than the Christians’ desire to abstain from worldly things. Today we see a version of neoliberalism that centers on a politics of the self. It’s no longer about acting in society’s best interests. Politics is nothing more than a pandering to individual’s private desires.

This project was assembled at Sculpture Space, where as artist-in-residence I was researching the sculptural dimensions of olfactory space. Left to their own devices, smells do not respect boundaries, which means designing a device to transmit and contain the scent within the installation. The scent transmission device in this artwork was the balloons themselves; prior to inflating them I coated the interior of some of the balloons with scented “halitosis” material and then relied on the gradual deflation of the balloon to transmit the scent via micro-perforations in the mylar. The result connects activity—the literal and figurative effort of world-making—to the breath. Breathing is fundamental to life, yet it is often just treated as a by-product of living. The long, uneven, and smelly “exhale” of the balloons slowly and melodramatically manufacturers a “last breath,” as it simultaneously elaborates on a history of inflatable art from Warhol to Koons to Huyghe.