... when art changes (on science/art collaborations) / August 6, 2017

Glimpses from the 2017 Eureka International Certificate Program, Siracusa, Italy.

“Most artists, of course, as less keenly interested in ambiguity of identity and purpose than I am. Open-endedness, to me, is democratic and challenges the mind. To others, it is simply waffling and irresponsible. It depends on what kind of art one is talking about. And on what segment of the public. When art as a practice is intentionally blurred with the multitude of other identities and actives we like to call life, it becomes subject to all the problems, conditions, and limitations of those activities, as well as their unique freedoms… The means by which we measure success and failure in such fleeting art must obviously shift from the aesthetics of the self-contained painting or sculpture, regardless of its symbolic reference to the world outside of it, to the ethics and practicalities of those social domains it crosses into. ”

Allan Kaprow wrote the above in an essay titled, Success and Failure When Art Changes. In the essay, which was published in the mid-90s, he was thinking back on an experimental art/education collaboration from 25 years earlier. I have always admired the ambiguity in Allan’s art and been entertained by his ability to articulate that ambiguity with paradoxical precision in his writing. Lately I have been thinking more and more about it in the context of how 1) I can expose new publics to art and 2) how, through non-art collaborations I can take art into other branches of knowledge for the purposes of new interdisciplinary forms for which no name currently exists. Related to this, obviously, is the question of evaluation; how does one measure success in these new forms? Recently, I had the opportunity to answer that question for myself, at least as it related to one collaboration that has been recurring for the past six years.

In 2011, Anna van Suchtelen and I were invited to be observers at the Eureka Institute for Translational Medicine. Eureka's course is an intensive residency that brings together 30 post-doctoral "students" (they are highly successful scientists in their own right) with nearly as many elite faculty members to engage a remarkable curriculum designed to prepare the emerging practitioners for the obvious and latent challenges they will face attempting to improve health and fight disease. It was expected that Anna and I would produce an artwork that somehow engaged the themes and dynamics of the course. For our efforts we produced the video, When to Throw a Painting to a Drowning Man. Instead of considering art and science as binary opposites, our video pointed to the commonalities of innovation and uncertainty in the practices of art and science. When the video was complete, we screened it to the Eureka community. It was successful by film screening standards; it stoked dialog, and in general, the audience seemed more cheerful when they left than when they arrived. But the video did little to suggest that art could be useful (in an integrative manner) to other branches of knowledge.

Perhaps because our video was a bit didactic, two years later we were invited to participate as members of the faculty. We translated our video into a 3-hour workshop and an interactive card deck. The workshop blended lecture and discussion with a heavy dose of improvised performance (and subsequent reflection on what just happened). The card deck instigated all the activities and commemorated the project, allowing for future engagement. The overall result was far more useful to Eureka’s program (as evidenced by student evaluations and anecdotal experiences that have been related throughout the years). Anna and I were still commissioned to produce an edition of art objects, but the objects took on the characteristic of a memory device which pointed back to the dynamic workshop. So was the workshop art? I’d say so, but I also don’t care much about labels provided the work produced the desired results.

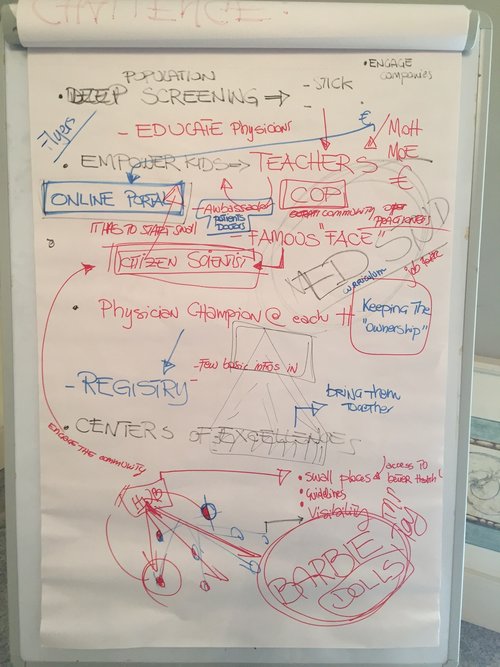

With each new year it seemed as if we were integrated slightly more into the Eureka program. This year’s course (2017) was particularly memorable. Eureka had brought in an energetic social impact coordinator and few outstanding alumni as junior faculty members. Their presence added a sense of urgency to the curriculum. Throughout the course, students developed group projects on regionally sensitive healthcare issues. A common goal was a patient-centered, preventative approach that would improve medical research and healthcare delivery. I was delighted to observe this aspect of the course, in part, because of the dominant role team-building and creative problem solving played in the development and execution of each group’s project. The final presentations were astonishing in the way students used performance to narrate a healthcare problem and solution, and create an impact that was both cognitively and emotionally resonant. (Unaccredited) BFA degrees for everyone!